New research reveals that bumblebees aren’t just fuzzy pollinators; they possess a surprising ability to understand time durations – akin to learning a simplified form of Morse code. In a breakthrough study, scientists at Queen Mary University of London taught these tiny insects to associate specific light flashes with sugary rewards, proving they can process temporal information in a way previously thought exclusive to vertebrates.

This discovery shatters the notion that complex cognitive abilities are limited to larger brains. Scientists have been increasingly amazed by the hidden depths of bee cognition in recent years. Bumblebees have been observed practicing a rudimentary form of farming, collaboratively solving puzzles, and even demonstrating basic mathematical concepts.

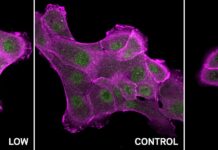

But recognizing time duration adds another layer to their impressive intellect. This skill is crucial for numerous survival tasks, from locating food sources and attracting mates to evading predators. To test this theory, the researchers designed an experiment utilizing a small foraging arena with a screen displaying two flashing lights – one longer, one shorter – each representing different durations like short (0.5 seconds) versus long (2.5 seconds).

One flash correlated with a sweet nectar reward, while the other signaled a bitter quinine solution—a decidedly unappealing treat for bees. The duration cues were randomly assigned to rewards across different bee groups, ensuring no inherent preference influenced their learning process.

Initially, the bees navigated the maze towards the flashing light associated with sugar until they achieved a success rate of 15 out of 20 correct choices. The crucial next step involved removing the reward altogether, forcing the bees to rely solely on their learned association between duration and sweetness. They consistently chose the flash pattern linked to the previous reward at a rate exceeding chance probability, clearly demonstrating they had successfully learned the timing patterns.

While impressive, the exact mechanism behind this temporal perception remains elusive.

“Since bees don’t typically encounter flashing stimuli in their natural environment, it’s remarkable that they could learn this,” says behavioral scientist Alex Davidson from Queen Mary University of London. “It suggests either an adaptation of existing time processing for movement or communication, or a fundamental neuronal property shared across species.”

Further research is needed to untangle this mystery. Nonetheless, this discovery underscores the boundless capacity for complex thought within seemingly simple creatures, reminding us that our understanding of animal intelligence may be vastly underestimating the capabilities hidden in miniature brains.