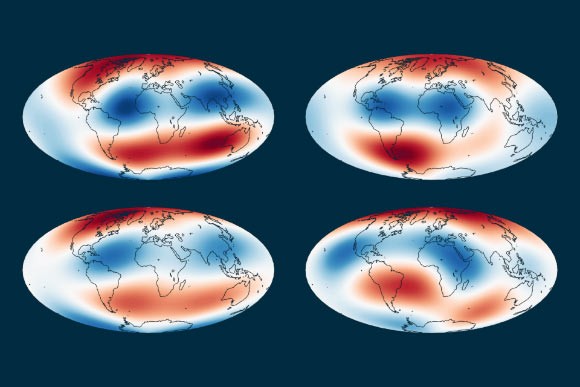

Two massive, intensely hot structures deep within Earth’s mantle – located beneath Africa and the Pacific Ocean at roughly 2,900 kilometers depth – have exerted a long-term influence on the planet’s magnetic field for hundreds of millions of years. A new study led by Professor Andy Biggin at the University of Liverpool reveals these structures create thermal contrasts at the core-mantle boundary, impacting how liquid iron flows and generates the magnetic field.

Understanding the Geodynamo

Earth’s magnetic field is created by the geodynamo: the movement of molten iron in the outer core. This process is similar to how a turbine generates electricity from flowing water or steam. But the core isn’t uniform; temperature variations are key. Researchers combined ancient magnetic field recordings (paleomagnetism) with advanced computer simulations to reconstruct how these deep-Earth features have shaped the magnetic field over 265 million years.

Thermal Contrasts and Core Stagnation

The simulations show that the outer core’s upper layer isn’t a consistent temperature. Instead, localized hot spots capped by continent-sized rock structures exist. Beneath these hot regions, the liquid iron in the core may slow down or even stagnate, rather than flowing vigorously as it does under cooler areas. This means that some parts of the magnetic field have remained stable for immense periods, while others have shifted dramatically over time.

“These findings suggest strong temperature contrasts exist in the rocky mantle just above the core,” Professor Biggin explained. “This affects how liquid iron flows, influencing the magnetic field’s stability.”

Implications for Earth’s History

This discovery has broad implications for several scientific fields. For example, understanding how the magnetic field has changed can help clarify the breakup of ancient supercontinents like Pangea. The magnetic field’s behavior is also linked to ancient climates, the evolution of life, and even the formation of mineral deposits.

Previously, many scientists assumed the Earth’s magnetic field behaved like a perfect bar magnet over long periods. This study challenges that assumption. The findings suggest the magnetic field is more dynamic, shaped by deep-Earth processes that aren’t uniform.

This research emphasizes that the ancient magnetic field wasn’t always perfectly aligned with Earth’s rotational axis, meaning long-term averages can be misleading. These results strengthen the use of paleomagnetic records to understand the evolution of the deep Earth and its stable properties.

The study was published in Nature Geoscience on February 3, 2026 (doi: 10.1038/s41561-025-01910-1).

In conclusion, these newly discovered deep-Earth structures are not just geological features; they are critical drivers of long-term magnetic field stability, influencing everything from continental drift to ancient climate patterns. Further research is needed to fully understand the interactions between these structures and the core, but this study provides a crucial new insight into Earth’s dynamic interior.