The European Space Agency’s Solar Orbiter has given us our first close-up look at the sun’s south polar region, revealing something surprising: its magnetic field is shifting toward the poles much faster than scientists anticipated.

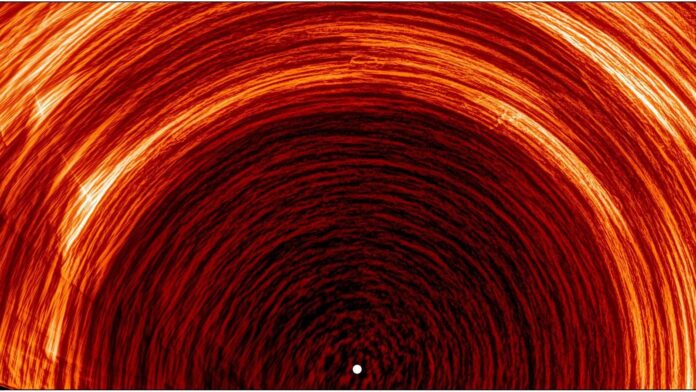

This discovery comes from a composite image built from eight days of observations taken in March when the spacecraft tilted its orbit to finally reveal this hidden area of the sun. The image shows bright arcs sweeping around the pole – glowing trails left behind by magnetic structures hurtling towards the sun’s edge at unusually high speeds.

Understanding the sun’s magnetism is crucial because it drives the entire 11-year solar cycle. This cycle sees magnetic fields twist, flip, and rebuild, powering everything from sunspots and solar flares to massive storms that can disrupt Earth. At its core lies a slow “magnetic conveyor belt” of plasma currents. These currents carry magnetic field lines from the sun’s equator towards the poles near the surface, then back down toward the equator deep within the sun. This continuous circulation sustains the entire magnetic field, but the processes happening at the poles have remained largely mysterious.

Before Solar Orbiter, directly observing the sun’s poles was impossible from Earth, and most spacecraft have orbited in a plane close to the equator. This made studying these critical regions difficult. However, Solar Orbiter’s unique tilted orbit provided that first clear view over the southern limb of our star in March 2025.

Using data from two key instruments – the Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager (PHI) and the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) – scientists were able to track how hot plasma and magnetic fields move across the solar surface. Their focus was the chromosphere, where these magnetic structures leave visible traces as bright, elongated arcs.

The results are remarkable: gigantic “supergranules” – bubbles of churning plasma each two to three times the size of Earth – are propelling magnetic fields toward the poles at speeds of 20 to 45 miles per hour (32 to 72 kilometers per hour). This is nearly as fast as similar flows near the equator, far exceeding what models had predicted.

“The supergranules at the poles act like a tracer,” explains Lakshmi Pradeep Chitta, lead researcher on the study. “They make the polar component of the sun’s global, eleven-year circulation visible for the first time.”

This groundbreaking research marks a new chapter in understanding our sun’s behavior. By finally illuminating these previously hidden polar regions, Solar Orbiter is providing crucial data about the engine driving the solar cycle and shaping the entire solar system’s magnetic field.