The Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in 2011 created an extreme environment, yet the microbial life found within the reactor remains surprisingly… ordinary. A 2024 study revealed that the bacteria thriving in the highly radioactive water of the plant’s torus room haven’t evolved any special adaptations to cope with radiation. This isn’t just a curiosity; it highlights a practical problem for nuclear decommissioning, where microbial activity can accelerate corrosion and complicate cleanup efforts.

The Accident and Its Aftermath

On March 11, 2011, a massive underwater earthquake triggered a tsunami that overwhelmed the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station. Core meltdowns occurred as seawater flooded the facility, leading to widespread contamination. The town of Ōkuma, where the plant is located, was evacuated, and remains sparsely repopulated to this day.

The Unexpected Microbial Community

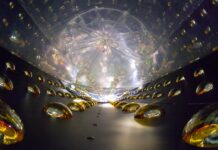

Engineers noticed microbial mats growing in the radioactive water accumulating inside the reactor buildings. Given that extreme radiation typically drives rapid evolution in organisms, scientists expected to find highly radiation-resistant species like Deinococcus radiodurans dominating the environment. Instead, they found the microbial communities were composed largely of common marine bacteria from the Limnobacter and Brevirhabdus genera, which normally feed on sulfur and manganese.

Why This Matters

The fact that these microbes haven’t adapted to radiation suggests that the levels weren’t high enough to select for more resistant strains. But more importantly, these bacteria form biofilms: slimy, protective matrices that shield them from radiation and accelerate metal corrosion.

“If biofilm-building microbes are the ones most likely to survive in radioactive waters, then that presents a predictable complication to consider during nuclear power plant decommissioning,” the researchers noted.

Implications for Decommissioning

Nuclear plant decommissioning is a decades-long process. Microbes can exacerbate corrosion, reducing structural integrity, and complicate cleanup by reducing visibility in water. The Fukushima microbes didn’t need extreme adaptations to survive; they simply exploited an environment where ordinary bacteria could thrive.

This discovery underscores that even without dramatic evolutionary changes, microbial life can pose a significant practical challenge in the long-term management of nuclear waste and facility decommissioning. Ignoring these resilient communities could delay cleanup and increase costs.