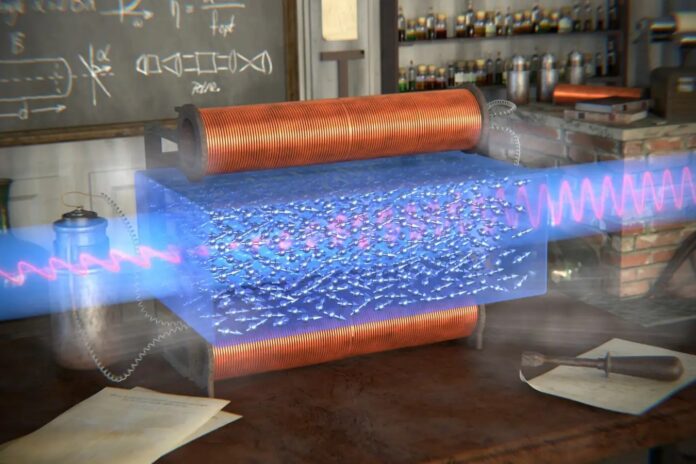

For nearly two centuries, the connection between light, magnetism, and materials has been understood through the Faraday effect —a phenomenon observed first by Michael Faraday in 1845. New research now suggests this relationship is more nuanced than previously believed, with the magnetic component of light playing a surprisingly significant role in how it interacts with certain materials.

The Original Faraday Effect: A Historical Overview

Faraday discovered that when light passes through certain substances (like glass laced with boracic acid and lead oxide) while exposed to a magnetic field, its polarization rotates. The established explanation held that this rotation occurred due to the interaction between the magnetic field, electric charges within the material, and the electric component of light itself.

The assumption was that the magnetic component of light had little to no effect. This has been the accepted model for almost two centuries.

New Findings: The Magnetic Component Steps Forward

Researchers Amir Capua and Benjamin Assouline at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem have challenged this long-held assumption. Their calculations demonstrate that, under specific conditions, the magnetic component of light does interact with materials, potentially accounting for a substantial portion of the observed Faraday effect.

The key lies in the polarization of light. When light is circularly polarized —meaning its magnetic field spirals like a corkscrew—it interacts more strongly with the magnetic spins within certain materials.

Terbium Gallium Garnet (TGG): A Revealing Case Study

The researchers found that when repeating Faraday’s experiment using Terbium Gallium Garnet (TGG), a magnetic material, the magnetic interaction could account for 17% of the effect with visible light and up to 70% with infrared light. This suggests that in some materials, the magnetic component of light’s influence is far from negligible.

This wasn’t previously investigated because magnetic forces within materials like Faraday’s glass are relatively weak compared to electric forces. Also, the spins in these materials don’t always align with the magnetic component of light. But circularly polarized light changes this dynamic.

Implications and Future Applications

Igor Rozhansky, a physicist at the University of Manchester, confirms the calculations are convincing and warrant further experimental verification. The findings open up new avenues for manipulating spins within materials, potentially leading to advancements in technologies like spin-based sensors and hard drives.

The ability to control magnetic spins using light could revolutionize data storage and sensing technologies.

In conclusion, the relationship between light and magnetism, first illuminated by Faraday, is now revealed to be even more intricate than previously understood. The magnetic component of light, long dismissed as insignificant, may hold the key to manipulating materials at a fundamental level, heralding a new era of spin-based technologies.