In November 1967, a graduate student named Jocelyn Bell Burnell made an astonishing discovery that would reshape our understanding of the universe: the first evidence of pulsars, rapidly spinning neutron stars that emit beams of radio waves. However, the Nobel Prize for this breakthrough went to her advisor, Antony Hewish, sparking decades of debate about credit and recognition in scientific research.

The Accidental Discovery

Bell Burnell was meticulously analyzing data from a newly constructed radio telescope at the Mullard Radio Astronomy Observatory in England. The telescope itself was an unconventional setup – a sprawling network of wires and cables, resembling a giant pea-plant frame, designed to scan the skies for faint radio signals. Working almost single-handedly, she noticed a peculiar recurring “scruff” in the data, a signal that she playfully nicknamed “LGM” (little green men) as a placeholder for an unknown source.

For weeks, this signal persisted, appearing intermittently from a specific region of space. When she brought her findings to Hewish, the response was dismissive: the anomaly was likely just noise, and she needed more efficient recording equipment. But Bell Burnell persisted, and soon after, she detected a clear, repeating pulse every 1.3 seconds. This was not interference; it was something entirely new.

Confirmation and Initial Skepticism

The duo confirmed the signal’s consistency and ruled out conventional explanations. It wasn’t terrestrial interference, nor did it match any known astronomical phenomena. Soon, they identified similar signals from other parts of the sky, leading them to publish their findings in Nature. The announcement triggered a media frenzy, fueled by speculation about extraterrestrial life, which Bell Burnell recalled being met with absurdly sexist questions from journalists.

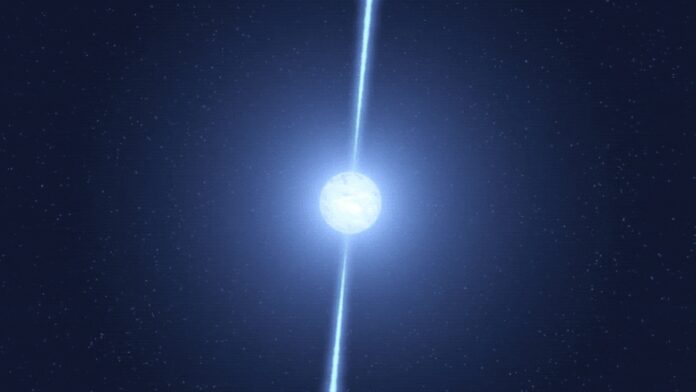

The scientific community was initially skeptical. However, by 1968, astrophysicist Thomas Gold proposed the correct explanation: the signals originated from pulsars – ultra-dense neutron stars left over after supernova explosions. These stars spin rapidly, emitting focused beams of radiation like cosmic lighthouses. The misalignment of their magnetic fields with their rotational axes creates the periodic bursts of energy detected by Bell Burnell’s telescope.

The Nobel Snub and Its Aftermath

In 1974, Antony Hewish shared the Nobel Prize in Physics with Martin Ryle for the discovery of pulsars. Bell Burnell, the original observer and primary analyst of the data, was excluded from the award. This omission led to widespread criticism, with some calling the prizes the “No-Bell Prizes.”

Bell Burnell herself took the snub with characteristic grace. She acknowledged the ambiguity of assigning credit in research, suggesting that Nobel awards rarely recognize students’ contributions. “I am not myself upset about it — after all, I am in good company, am I not?” she joked, alluding to other overlooked researchers.

The story of Jocelyn Bell Burnell serves as a cautionary tale about the power dynamics in science and the systemic biases that can prevent recognition for early-career researchers, particularly women. Today, Bell Burnell is widely celebrated for her work, and her legacy continues to inspire astronomers worldwide. She received the Special Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics in 2018 and donated the entire $3 million award to fund scholarships for underrepresented students in physics.