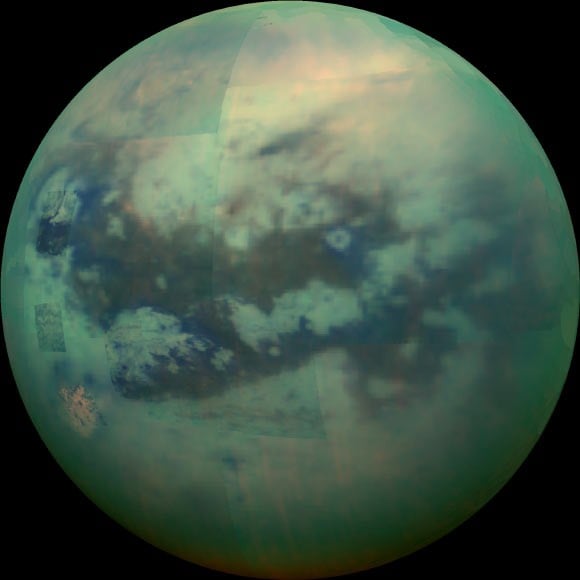

Recent research casts doubt on the long-held theory of a vast subsurface ocean on Saturn’s moon Titan. Data from NASA’s Cassini mission, once interpreted as evidence for a global ocean of liquid water, now points to a more complex interior structure – likely a thick, slushy layer rather than an open liquid body. This finding challenges earlier assumptions about Titan’s internal dynamics and how it responds to Saturn’s gravitational forces.

The Cassini Mission and Initial Findings

For nearly two decades, the Cassini mission collected extensive data on Saturn and its moons. Early analysis suggested a deep ocean beneath Titan’s icy shell, based on observed deformations in the moon’s shape as it orbited Saturn. The idea was that a liquid ocean would allow Titan’s crust to flex more under Saturn’s pull. However, these initial conclusions didn’t fully align with the physical properties derived from the data.

The Key: Timing and Viscosity

The breakthrough came from re-examining the timing of Titan’s shape-shifting. Researchers, led by Baptiste Journaux at the University of Washington, discovered a 15-hour delay between Saturn’s peak gravitational pull and Titan’s response. This delay suggests a highly viscous interior, meaning it takes significant energy to deform the moon.

“The amount of energy lost inside Titan was much greater than the researchers expected to see in the global ocean scenario.” – Dr. Flavio Petricca, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

This level of energy dissipation is incompatible with a simple, liquid-filled ocean. Instead, the new model proposes a thick, slushy layer containing water and ice under immense pressure.

Why This Matters

Titan is unique in our solar system as the only world besides Earth known to have stable liquid on its surface. However, this liquid isn’t water; it’s methane, due to the moon’s frigid temperatures of around -183°C (-297°F). Understanding Titan’s internal structure is crucial because it informs our understanding of planetary evolution and the potential for subsurface environments that could harbor complex chemistry.

The findings also highlight the importance of refining scientific models when new data emerges. What once seemed like a clear-cut case for a global ocean now appears to be far more nuanced.

The New Model: Slush, Not Ocean

The revised model suggests that the watery layer on Titan is so thick and under such immense pressure that water behaves differently than it does on Earth. The slushy consistency explains the observed lag in deformation while still allowing for some degree of shape-shifting under Saturn’s pull. This discovery significantly alters the scientific community’s perception of Titan’s interior composition.

The study, published in Nature, provides strong evidence against the previous hypothesis, opening new avenues for research into the moon’s complex internal dynamics.

The findings underscore that even seemingly well-established theories must be revisited as new evidence emerges. Titan’s interior remains a dynamic and intriguing area of study.